When I was seventeen, my mother started getting intense angina attacks whenever she walked up the flight of six stairs in our house. Her two brothers had just died of heart attacks, one in his forties and the other in his fifties, prompting me to become a vegetarian. My grandparents had died, mostly of heart disease, before I was born, and all the men on my father’s side of the family died in their fifties. And now I was scared of losing my mother. I said, “Mom, I’m giving up meat and you should, too. It killed your brothers, don’t let it kill you.” And she gave up red meat, though she didn’t yet give up chicken, fish, or dairy.

When I was seventeen, my mother started getting intense angina attacks whenever she walked up the flight of six stairs in our house. Her two brothers had just died of heart attacks, one in his forties and the other in his fifties, prompting me to become a vegetarian. My grandparents had died, mostly of heart disease, before I was born, and all the men on my father’s side of the family died in their fifties. And now I was scared of losing my mother. I said, “Mom, I’m giving up meat and you should, too. It killed your brothers, don’t let it kill you.” And she gave up red meat, though she didn’t yet give up chicken, fish, or dairy.

She was fifty-four years old at the time. I think about that now, at fifty-eight, and I can only imagine how scary it must have been to lose two brothers to heart disease within months and then get terrible chest pains walking up a short flight of stairs. She wasn’t overweight, or at least not more than a few pounds. She didn’t smoke. It would have easy to conclude that she just had terrible genes for heart disease and was doomed to have a short life.

Her doctor put her on a regimen of statin drugs and aspirin while she made her modest dietary changes. She didn’t go to doctors too often, although she did actually once manage to save my father’s life by making an appointment for herself with a dermatologist. She waits for the dermatologist in his office; he enters and says, “What can I help you with, Mrs. Merzer?” She says, “My husband. He’s in the waiting room.” The dermatologist goes into the waiting room and beckons my father into his office, where he examines and biopsies a growth on my father’s cheek that my father was unconcerned with. It was melanoma. He had an operation to remove all traces of the cancer more deeply at a hospital in Manhattan. I accompanied my parents, and just after leaving the hospital, as we’re crossing the street, my father with rare emotion embraces my mother and says, “Dottie, I’ll never forget that you saved my life. I will thank you every day for the rest of my life!” My mother breaks the embrace and says, “We’re in the middle of the street, you’re going to get us killed!”

Cut to about ten years later; my folks have just retired to Florida. I visit them, and they get in a fight over something stupid, as they occasionally did. My father’s very upset with my mother. I try to intervene by saying, “Pop, don’t you remember that day in Manhattan when you had the operation for melanoma and you embraced Mom in the middle of the street and told her that you would thank her every day for the rest of your life for saving your life?” He pauses a good long time. Then he says, “It doesn’t ring a bell.”

My father saved my mother’s life, too. In Florida, at about the age of seventy, she got a new cardiologist, the son of a childhood friend of hers. He does a scan of her arteries and tells her she has a 90% blockage and needs an immediate, emergency angioplasty. My father says, “Don’t listen to him; he’s just trying to make money. If you listen to him, I may have to divorce you.” The doctor becomes furious. “Who are you going to listen to, him or me? I’m a doctor; he’s not a doctor!” My mother says, “I’m going to listen to my husband; I don’t want to get divorced.” She never had the angioplasty, and the doctor “fired” her, refusing to ever see her again. I told her to get stricter with her diet, and become a real vegetarian. She adjusted her diet to give up chicken and almost entirely give up fish.

My father developed Parkinson’s, and when my parents were about eighty-six, I moved them both to California so I could help take care of him. I also took my mother to doctors, from whom she got about a half-dozen prescriptions, mostly for blood pressure and for her heart condition. And I started doing their food shopping and so willy-nilly they became low-fat vegans.

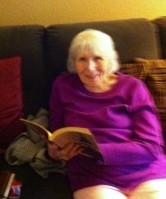

Parkinson’s took my father’s life at the age of eighty-eight, but he died with a strong heart. My vegan mother is today ninety-five-and-a-half. She has never had a cardiac event; I think we can say with confidence at this point that my father was right that she didn’t need that angioplasty twenty-five years ago. She just visited the doctor last week. He took her off her last medication; she now takes no drugs for anything. She has no need for adult diapers. Her mind is fully intact, and she reads a novel a week. She’s frail, and she has a walker, but she uses it mostly for exercise: she puts it in the living room, where she walks around it; then occasionally she moves it to the bedroom, and she walks around it there.

I wrote my first novel last year and gave it to her in the fall to be its first reader. She read it in a week. I asked her what she thought. She said, “It was good. Are you going to bring me another one next week? I’m running out of books.”

Click to contact Glen Merzer!